George Criddle (born. 1984) is a British-Australian artist, writer, and occasional curator currently lecturing at La Trobe University in Bendigo. They completed a PhD in 2021 at Monash University and have previously studied at Curtin University in Perth and École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Since 2005 George has been part of international exhibitions and residencies in Kassel, Zurich, Paris and Prague as well as exhibitions in Melbourne at The Living Museum of the West, MADA faculty Gallery, Margaret Lawrence Gallery, and artist-run spaces such as Kings, West Space, Blindside, Slopes gallery and TCB gallery. They are currently on the board of KINGS Artist Run Gallery as Co-ordinator of the Emerging Writers Program with Beatrice Rubio-Gabriel.

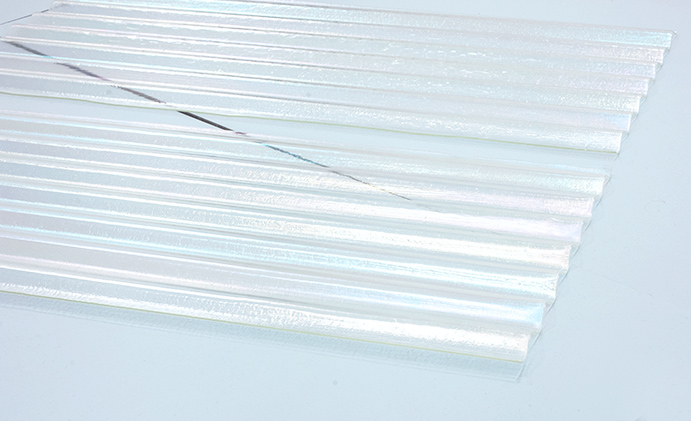

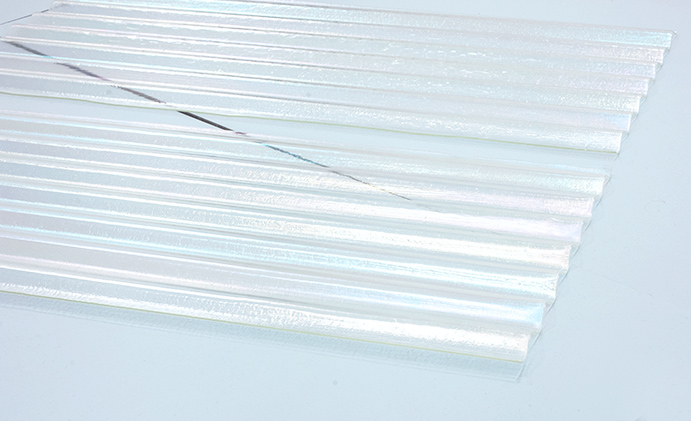

Linger is both an invitation and a description. It is what the artist – any artist – asks of their viewer: pause, take a moment, consider this. Don’t move on just yet. It is also, in the case of Georgina Criddle’s practice, a description of the artist’s process of making. Criddle’s is a deeply thoughtful practice, and a durational one. Her works unfold slowly: intuition, memory, and responsiveness to space and material all come into play in this process of tangible thought.Linger gives a fractured view, an oblique reflection, of an absent subject. Criddle has taken as her starting point a strange, subterranean structure: an amputated fragment of a building, a basement for a house that is no longer there. This odd, forlorn architectural appendage still exists somewhere in the Czech Republic. It probably isn’t a fragment any more, it has probably been joined up to a new building by now, but when Criddle encountered it 3 years ago, there it was, buried in the earth, an orphaned basement. Like a subconscious mind without its consciousness. Somebody had built a little corrugated iron pitched roof over it to keep the rain out and this made it even more strange: attic and basement together, a compacted house, sunk into the ground.

As a memory, this amputee basement has been unusually persistent. Perhaps simply because of its very strangeness, its deviation from the ways we habitually experience space and architecture, it struck a chord. As a figure for a lost structure, the persistent trace of something that was there but now is not, it continues to surface in Criddle’s work, she continues to worry away at it, gently but insistently.

It is interesting to think about how things, thoughts and experiences can be transformed and translated into new things, and new experiences. There will always be unexpected gains and losses in this process. Slippages and accidents of speech will occur; the translation will take on a life of its own. As Criddle pointed out to me once in conversation, the best translations convey the affect of the original rather than forming an exact or ‘correct’ reproduction. In this sense, material transformations are no less slippery than words. Both words and objects contain the traces of their making; they are etymological or material palimpsests. While a word or an object can take on a new form, it will also index, in its very structure, the way it came to be. Communication is always fraught with these buried traces, which can sometimes resurface and disrupt the clarity of what you are trying to say.

But, as Linger demonstrates, it is in the process of reflection – which is always a refraction, always imperfect or oblique – that new things can be made. A material language can emerge from this durational process, one which might talk about displacement, or gains and losses, or clarity and opacity, or the cracks between things. With reflection, the process of making becomes responsive, and objects become aggregates of past and present. New ideas are laid over old ones, and new materials might take the shape of old, inheriting the memory of a particular form. One architectural space can be restaged, obliquely, as a series of ephemeral traces – a corrugated roof, a feeling of precariousness, a lack of visibility – inside another. This is a fragile construction, as light as air. It reveals itself slowly, but also responsively. Taking its character from its new surroundings as well as from the process of making, it concentrates duration into tangible form.

Anna Parlane